"It

is impossible for ideas to compete in the marketplace if no forum for

��their presentation is provided or available." �������� �Thomas Mann, 1896

Office Planning & Design�

Author:�

John Hathaway-Bates with Lawrence Lerner

Commissioned and written for:

The American Management Association

�

Introduction�

Office planning has a direct effect on the productivity of the employees who use a business environment and, if done properly, can bring benefits to all sectors of an organization. Personnel Executives will find that the management of human resources is made much easier if the environment is geared to the needs and productivity of the individuals the organization employs. Similarly, Administration Executives will find that accuracy and productivity increase in a direct relationship to the efficiency of communications, both within and between departments.

Business can thrive with change - by either growing or contracting, within departments, divisions, or the total organization - and the application of professional office planning techniques provides the tools to allow this change to occur with the minimum of interference of day-to-day activities, without sporadic budget demands to accommodate capital investment needed for expansion. Space Planning is an economic necessity, as it enables the organization to employ its resources in space totally and in a functionally efficient manner. Good office design is a combination of function, logistics, economics, and aesthetics. No administrative complex can be planned from one single point of view. Office planning is a science that employs many disciplines, brought together to serve business needs in today's technological world. Executives who are responsible for office planning or facilities management have one of the most important tasks in any organization, and much of their success or failure will depend to a great extent on their ability to keep up with the technological advances in this area. Also important is the strength of the advice and assistance that they can call upon to develop solutions to ever-changing needs. �

This course will not train managers to be office planners or interior designers. Rather, it is formulated to assist executives in efficient management of their company's space resources and to introduce them to the terminology, systems, and techniques of the office planning profession. Such information will enable executives not only to understand but also to implement the benefits of good facilities, planning, and management.

�

Chapter One: Office Planning & Design

Evaluating Organizational Factors: The Criteria for Location Selection

The first lesson any executive involved with office planning must learn is that an organization, whether it employs 50,000 or only five, is a growing entity. It has its own life, its own patterns. As the company experiences its daily life, the organization develops as the joint response to the daily situations experienced by all members of the organization. In the words of Shakespeare, "All Past is Prologue" and this probably applies more to an organization of many individuals than it does to a single individual who can impose arbitrary personal decisions upon change.�

An executive involved in office planning is providing a working and living environment for other human beings. The executive must, therefore, bear in mind that, for many people, the workplace occupies as much of their time as does their home, and they relate to it in a similar manner. Before any reorganization, relocation, or juggling of the people in an office space can be undertaken, the executive involved should have a thorough knowledge of the organization. This knowledge cannot be based on a few months' or even a few years' data; it must instead reflect the total history of the organization.�

Just

as a person cannot be evaluated adequately on the basis of a five-minute

conversation or short friendship, so too is it impossible to judge an

organization based on a short acquaintanceship. The procedures used for

obtaining in-depth information about the organization are described in this

chapter. How these procedures fit into the overall planning process can be seen

by studying the "Space Planning and Design Procedures Outline"

presented in the Appendix (part I, in particular).

�

There are many formulas for evaluating the growth patterns and life cycle of an organization. The simplest is to establish a basic history pattern in graph form. Let us assume that Henry Smith, a manager of ABC Corporation, would like to develop just such a graph. First he would have to obtain and analyze certain information normally held within personnel or accounting departments, according to the following procedures:�

-

Obtain the annual reports of the organization as far back as possible.

-

Analyze the personnel files, listing numbers of people employed per department and the quality of their expertise, through the life of the organization, year by year.

-

Plot the turnover figures of the company and the growth of the company by means of management accounts. From these data, Smith will be able to plot simple graphs based on particular material extracted from his research. For example, for every year, he can plot the total sales volume figures. He can then plot a graph showing numbers em�ployed per department to achieve these sales figures, and a further graph showing capital expenditure required.�

In other words, Smith can build up in simplified form the growth and history of his organization. Onto this graph, he can also enter relevant highlights, such as the opening of a new subsidiary company or branch office, or the introduction of new products. Developing such a graph is not as difficult a task as it sounds, and it presents the manager with a historical pattern that provides a meaningful context for today's experience and situations and enables the manager to evaluate possible future trends. Having established the basic history pattern of the organization, an executive then needs to know why the organization is where it is at present; that is, why the company decided to locate in the present building, town, state, and country.�

The reasons behind any organization's choice of location at any time are directly related to one or more of the following possibilities:�

-

The company was established in the area owing to the presence of its founder or the raw materials necessary for it to come into being.

-

The company is engaged in a particular activity that, by tradition, is located in a given area.�

-

The company was located in the area because of financial benefits.�

-

The specialists, craftspeople, or staff required are more available at the present location than they were in any other location at the time of the company's establishment.�

Obviously, the reasons behind the location of any administration of any organization are "of the moment". They can change for a myriad of reasons with the passage of time; therefore, just because a company is now established in a particular area or city does not necessarily mean that it will always need to be located there. In fact, studies have shown that, quite often, organizations remain in an area long after the reasons for their being there have disappeared.�

Once the reasons why a company is located where it is at present are established, the executive will realize that there are many contributing factors, seemingly minor when viewed out of context, which, in fact, could cause great upheaval if the company were relocated. If, however, no more space is available on the present site and the company needs to expand, or if the staff required are no longer available at the current location, then the executive has little choice but to look for other premises. However, before doing this or suggesting this to the powers that be, the executive should evaluate the present location against all other possibilities.�

There are eight main reasons for either staying at the present site or moving to another site, and thorough investigation of these factors must be given first priority before any reorganization or office planning is undertaken. Otherwise, the executive runs the risk of spending capital on these activities without dissipating the overall problems the organization faces. The eight main criteria for determining whether a company should remain in a given area or move to another location are the following:�

-

The availability of competent staff.�

-

The political stability of the area in relation to the business being conducted.

-

The benefits or lack of benefits of the tax system in the area.�

-

The availability of necessary raw materials.�

-

The convenience and economics of transporting the products of the company to the areas of demand for those same products.�

-

The ability of the company to expand or contract in any given situation.�

-

The energy costs in the area relative to productivity.�

-

The image for the company and its products that is associated with a particular area.�

All these points should be considered carefully at regular intervals to evaluate whether the organization is in the right place at the right time. If the answers to the given criteria are more negative than positive, then sooner or later relocation may be necessary. In any event, the subject of the location of any organization should be considered at regular intervals in comparison to other available locations.�

When evaluating any new site with respect to an existing site, the manager must always consider the cost and the scale of removing an administration to another location. Although a proposed relocation appears to be beneficial in the long run, the problems that a company can face in changing locations are often numerous in the short term. Such difficulties include loss of staff owing to human reaction against moving away from the familiar; loss of local contacts that "oil" day-to-day operations; and the disruption caused by trying to conduct a continuing business while organizing a new base of operations. However, if the financial situation can be balanced and the proper planning employed, there is no reason why the removal of a company into another city, state, or country cannot be undertaken with beneficial consequences.�

Quite often, reorganization on an existing site rather than relocation can be a satisfactory solution for an organization considering a move. The chances are that most organizations, unless pressed, will stay where they are for the sake of stability. Accepting this fact means that the executive in charge of office management or office planning is dealing with arbitrary spaces and arbitrary facts that he or she can do little to change except by reorganization. Therefore, the executive needs to evaluate the existing potential of the present site in relation to the proposed development of the organization over a specific period of time. �

Staff

Anyone involved in office planning must recognize at all times that an office exists only to house the administrative staff who service the organization. It is all too easy to forget to pay enough attention to the needs of people when dealing with numbers, equipment, and buildings. To engage in any serious consideration of office planning without employing a knowledge of behavioral psychology is a fundamental mistake and could lead to irreparable consequences.

Those who are in business recognize that an organization is only as efficient as the people within it can make it. If the people employed to operate an office, be it one room or a multi-floor building, are unhappy or feel that they have been stripped of their individuality, then productivity will suffer.

Compiling Staff Dossiers

The first task, therefore, of any executive involved in office planning is to ensure that a complete and detailed staff dossier exists for every person involved in the complex. No employee is too low in the structure of an organization to be ignored, for discontent can be sowed as easily by a part-time cleaner as it can by a long-term executive in middle management. Over the years, behavioral psychologists have developed a general format for evaluating individual profiles, one that allows executives involved in office planning to carry out their tasks efficiently.�

First the data detailed in Exhibit 1-1 must be obtained for every member of the staff who will be involved in a change in the organization's environment. This applies even to the reorganization of a small department. Governments, institutions, and associations have established certain protective legislation for employees; therefore, in some cases, the answers required can only be an executive evaluation.�

After the facts outlined in Exhibit 1-1 have been ascertained, the manager should receive from each employee's immediate superior an estimate of how that employee will respond to any proposed change. The response should fall into one of four categories:�

1. unqualified acceptance;�

2. compliance from necessity;�

3. dissatisfaction; or�

4. indifference.�

Obviously, the needs of the

organization always override the needs of individuals within it. Thus,

individual employee needs should be evaluated in terms of the company's ability

to recruit equal or better staff should such recruitment be necessary. Thus, if

the company exists because of the creativity of one man, then that man must be

provided for; however, in the normal state of affairs, few employees are truly

indispensable.�

Recruiting

Staff�

In addition to the financial reward system, a satisfying working environment attracts potential staff and retains present employees. Quite often, recruitment of staff is a major reason for the reorganization or redesign of office premises. The executive involved in office planning must bear this in mind and create efficient communication with the human resources director and personnel department to ensure that the benefits available can be communicated to existing and potential staff.�

Most companies rely on four main recruitment techniques:�

1. advertising in newspapers and professional publications;�

2. direct mailing to potential employees;�

3. recruiting with the assistance of specialist agencies; and�

4. obtaining recommendations from existing staff about potential employees.�

In all these areas, well-documented data regarding the office environment and conditions can only assist in the recruitment of staff. This applies to both positive and negative reactions that can be expected from potential employees. If applicants are fully aware of existing conditions and plans for the future, they will enter their prospective workplace equipped to evaluate their own future without first having to come to a conclusion about the decor, equipment and conditions.

A manager involved in office planning should also establish, to whatever extent is possible, what role the current office environment played in the successful recruitment of the present company staff. Such knowledge should be taken into account in future decisions so that staff acceptance of the environment is maintained or enhanced. The executive can also obtain from the present staff reasoning and advice on what changes need to be made to increase recruitment opportunities.�

It is important in any design or office planning decision to realize that staff are the raw material of the business, and their reaction both initially, when they first enter the facility, and daily, with their continual use of it is paramount to both their work enjoyment and their continued employment. It is logical, therefore, to locate the site of recruitment interviews of potential staff as near as possible to the entrance of the building, which is normally the most impressive area. When considering the location of interview rooms, the executive involved in office planning must always bear in mind what image of the company is being presented to potential employees. Sending them along endless corridors, past cleaning cupboards, or through busy offices is no way to overcome their initial uneasiness about the interview.�

Quite often, the extent of the personnel or human resources manager's involvement in office planning is that he or she is merely abreast of company decisions. This is unfortunate because, in fact the personnel director can provide great assistance to the office manager and office planner. The human resources director can, for example, establish what conditions prevail at the nearest competitors, these being the companies most likely to lure away better employees. He or she can also keep a record of the most productive staff's equipment relative to the least productive staff's equipment.�

The personnel manager can also convey to the office planner any problems that occur more often than should be expected. If certain segments of the company staff are continually complaining, it can be expected that they are comparing their lot to that of employees working for competing companies. Complaints are normally directed to the personnel manager and, unless a system of communication of these facts is established, the office planner will not learn about them. It is much easier to know what is necessary before reorganizing a department than to learn the facts afterwards, when it is too late to implement changes that could have solved the problem.

In conclusion, office planners and/or office managers should at all times realize that they are working with two separate entities:�

1.� the equipment and environment on which they can have some effect; and�

2.� the personnel employed to operate with that equipment and within that environment.�

Any office planning decision

directly affects these entities. Therefore, the executive should be acquainted

with the needs of people in the organization long before he or she makes even

the most basic design or planning decision.

�

EXHIBIT 1-1���� Data Necessary for Compiling Staff Dossiers for All Employees

. Identification Data

1. Name.

2. Immediate superior.

3. Department of employment.

4. Place of work.. Employment Data

1. Period of years with company.

2. Salary range.

3. Duties and responsibilities.

4. Age range.

5. Communication ability:

����� (a) Appearance.

����� (b) Speech.

����� (c) Disposition.. General Circumstances

1.� Previous employers (giving period of employment and position).

2.� Academic achievements and qualifications.

3.� Membership in professional or social institutions.

4.� Occupational and educational attainments.. Analysis of Present Working Conditions

1.� Personal furniture and equipment.

2.� Personal space allocation.

3.� Immediate working group (four names).

4.� Non-financial incentives.

5.� Nearest window with vision (in feet).

6.� Nearest rest room (in feet).

7.� Communication equipment.

8.� Keys held.. Activities Outside of Work

1. Involvement with organization's social activities.

2.�Leisure interests.

3. Marital status.

4. Number of children (with ages).

5. Other dependents (with ages).

Education Needs

Executives involved in office planning may be surprised to learn that they need to consider the educational facilities required by the staff employed in the office complex. It is also important from the recruitment director's point of view, to know the educational facilities available to staff for their children in the area where the office is located. Obviously, the office manager normally does not become too involved in this aspect of business; however, when planning offices,� whether new facilities or simply upgrading existing offices that will recruit extra staff, the manager must realize the importance of this factor. Therefore, he or she should, obtain and analyze all available in-house information on this subject from either: the personnel director or recruitment manager (or some appropriate source) and should understand its bearing on the location or growth of the office.

This subject can be divided into two basic sections dealing with the actual staff employed. The first concerns relocating an office to another site; the second involves increasing the capabilities of the staff employed within an existing facility. A further factor, which relates to the need of staff to find educational facilities for their children, will also be considered in this section.

Relocation

When relocating an office or moving a department to another location, the office planner must establish that any educational needs the company may require for its staff can be fulfilled in that new location. As has been stated before, location of any office facility is, to a large extent, dependent upon the availability of professionally qualified staff in that location. For example, an organization that needs computer analysts but is located several hundred miles away from the nearest college that trains computer analysts will have difficulty in attracting these people at the same cost as another organization within walking distance of the college.

The

growing recognition that educational qualifications are an asset has lead

to

ever-increasing enrollment of employees in adult training classes. Therefore,

before relocating an office, the planner must make sure that key staff being removed

to a new area will be able to continue in classes similar to those in which they

are already enrolled, if at all possible, and that new staff will have the facility

to increase their qualifications.

More and more companies are finding it necessary to institute their own training programs. To avoid setting up inappropriate training facilities, the office planner needs to be advised by each and every department of its training requirements. The establishment, for example, of a huge lecture theater when, in fact, only six people will be present at the majority of training sessions would be economic nonsense. Closing down and reorganizing any room within an office complex whenever the organization needs to run training sessions would also be inefficient. Therefore, establishing realistic data regarding training needs should be high on the priority list of any executive involved in planning.

Furthermore, the planner should determine what types of training programs can be implemented in the building. Professional advice should be sought on the specification of appropriate audiovisual equipment, if necessary. In addition, access to any training area should be independent of the everyday business of the organization and should be acoustically segregated from the normal activity of the building.

The simplest method of approaching the establishment of training facilities within a building is to isolate them visually, acoustically, and physically from the rest of the building. At the same time, the organization's image and standards should be maintained within the training area.

Updating an

Existing Facility

�

The most common need for office planning skills arises when an organization decides to update its facilities, either in total or by department. Accompanying such changes are alterations in the required skills of the staff that will use these facilities.

In the past, most employees were expected to obtain their educational qualifications before they were recruited, and any necessary additional training was conducted during the course of normal business activities. Over the last two or three decades, however, the technological skill needed by even the most junior member of the clerical staff has led to the implementation of in-house training programs. It has also been found that morale increases if employees feel that they are learning new techniques that will equip them for a more secure or more rewarding future. Therefore, today most companies make allowances for in-house training. Many major corporations maintain separate facilities for this purpose alone, in the form of training centers that are completely isolated from the normal everyday run of business and are operated as an individual department within the organization. However, for the smaller company, this approach is too expensive and impractical. Therefore, the planner should consider whether training facilities are a necessary component of the updating program. If they are, he or she should follow the procedures discussed in the previous section to isolate an area of the proper size and in the proper position within the overall matrix of the plan.

The executive involved in planning must always remember that, unless employees are properly trained and educated in the techniques that are essential to the proper functioning of the organization, then business must suffer. Therefore, it is up to the executive to investigate and discover the needs for training and then to implement them within the plans.

Transportation

When considering a new location for an office or using new work schedules or time periods within an organization, the executive involved in office planning must consider the transportation requirements of the people, equipment, and products travelling to and from the office. In fact, one does not even need to relocate an organization or change work schedules or time periods to become involved in the problems concerning efficiency of transportation. A company, simply by increasing the size of a single department, will increase the number of employees needing transportation to the office. Therefore, before beginning the actual office plan, the planner should determine what difficulties employees will encounter in getting to the workplace.

It is generally, though perhaps mistakenly, believed that most employees prefer to drive to work in their own vehicles. This is based on the fact that many employees do have their own transportation; however, with rising energy costs, this situation is probably going to change.

Unfortunately, public transportation does not always supply a comparable alternative, and, in metropolitan areas where staff come in from many different places, the arrival times can vary by as much as an hour on trains and buses used by staff in the same department. As a non-financial incentive from their employees, many large companies now operate their own fleets of vehicles, which transport employees to and from various train and bus stations.�

Although, implementation of such programs is initially expensive, they will probably become more common as energy costs rise. Therefore, office planners have several conflicting facts to evaluate and analyze. They must:

1. Ensure that sufficient car parking is available for those employees who wish to use their own vehicles;�

2. Ensure that a "dropping off point" is established for those members of the staff who use car pools or shared transportation;

3. Evaluate the local transportation system upon which the company must rely to deliver staff and equipment to the premises.

In addition to considering the transportation systems that deliver people, the planner must also evaluate how everyday supplies required for the proper functioning of the office complex are to be delivered. There must be definite delivery "trails" within the plan to allow movement of materials from the reception point to the place of usage or storage.

The office must be seen as a center that controls many external supply lines of people, materials, equipment, supplies, and communications. Great care must be taken to ensure that the "perfect" office is able to function, not only in theory, but in actual daily use.

Relocation Costs

To isolate the individual

relocation costs, it is essential to obtain a true picture of the costs involved

in relocating either a department in an existing office lay�out or a complete

complex to a new location. Costs should be divided under the

following headings:

1. Social relocation costs of moving key personnel for example, transportation of household goods, airfares, and reimbursement for general expenses.

2. Packaging and transportation costs of materials, files, and equipment.

3. Cost of productive working hours lost.

Obviously,

productivity must fall if employees are involved in moving rather than

in fulfilling their normal function. Therefore, relocation to new offices is best

carried out over a holiday period (or, if this is impossible, employees are

asked to take whatever days are owed to them from their vacation allowance at this

time). When reorganization within an existing layout is undertaken, all major work

should be carried out either over a weekend or outside normal working hours.

Obviously, these are logical assumptions that cannot always be implemented,

but the executive involved in office planning should always try to consume as

few productive hours of the staff involved as possible.

The

major relocation costs of any project will normally be evaluated by the

accounting department; therefore, periodic consultation between the accounting

department

and the executives involved in office planning should be a regular

responsibility of both parties involved. Such meetings should be scheduled in addition

to all other financial meetings regarding the project. They need not be long,

but they should deal specifically with the costs of relocation and the hidden costs

of lost productivity during the transition period.

Telecommunication Systems & Mail Service

Companies today rely more and more on fast and efficient oral communication. As world trade becomes more necessary to the survival of companies, so telecommunications become increasingly important. Executives concerned with office planning must, therefore, consider the telecommunication needs of their organization and of every individual within it. Even before planning begins, these needs must be evaluated, based on the criteria provided by the heads of all departments within the organization.

The quickest, simplest, and most efficient method of obtaining input on telecommunication needs is to circulate a questionnaire to each department head requesting that he or she analyze departmental needs both now and in the foreseeable future to allow for their consideration in the overall plan.

Telephone Systems

The following facts need to be ascertained from each department head:���������������

1. How many phones are presently in use?

2. How many phones will be needed after reorganization?

3. How many phones will be needed in 12 month's time?

4. Which members of the department will require individual extensions, and how many?

5. How many shared extensions will be necessary (for multi-individual communication with an incoming call)?

6. How many phones will need loudspeaker facilities?

7. How many phones will need recording facilities?

8. How many phones will need 24 hour answering and recording facilities?

9. How many multi-digit numbers will be dialed direct (to evaluate whether memory dialing feature sets are required)?

10. How many phones need the ability to transfer calls?

11. How many individual/private lines are required?

12. What is the maximum number of calls the department receives at one time (to evaluate lines required)?

Internal Telephone Communication. �

Internal communication between individuals or departments is a separate need to that of external communication and, for security as well as efficiency, it is usually best to isolate one from the other. Clients or suppliers will soon become aggravated if they are unable to contact the particular extension they require because that extension is in constant use for internal communication.

Incoming

calls must always have priority and, therefore, should be directed to

independent receivers. This is not to say that internal communication is not

also important. Obviously, it is. Therefore, each department head must provide

the office planners with accurate information so that systems that allow

efficient interdepartmental

communication are installed.

All department heads should, therefore, answer as accurately as possible the following questions with respect to their department:

1. With which departments do you most regularly communicate? (If possible, give the number of calls on an average day to each individual department.)

2. Will any of these calls be shared (are they conference calls needing speaker or multi-extension connection)?

3. How many internal communications units are needed in your department?

4. Which members of your staff are authorized to make interdepartmental calls?

Telephone System Computer Units.�

Memory units have been developed that plug into a telephone system and retain individual numbers that can be automatically dialed by punching in the proper code. The planner must evaluate the time costs of the executives involved and the efficiency gained by keyboard operators to decide if these advanced machines will be useful to the organization.

Most telephone companies will give a presentation to the department heads to explain the systems that are available. It is in the interests of efficiency that such a seminar is set up before any decisions about possible systems are made. The executive involved in office planning should always bear in mind that the majority of department heads, although up to date with current information about their own discipline, are probably years behind in their knowledge of systems they do not use daily. Therefore, by calling in outside experts, the planner can avoid many hours of debate and argument about which system is most beneficial.

Telex Systems

Many companies throughout the world have telex and/or FAX transmitters. The planner should locate receivers for these services in the areas where they are most often used. Normally, the accounting department should have its own individual receiver/transmitter to ensure confidentiality of information communicated. The sales department should also have its own receiver/transmitter to ensure that inquiries and orders are dealt with promptly and efficiently. It is necessary, therefore, that the needs of the company, by department, are identified and examined in depth prior to starting any office planning.

Computer Systems

With the increase in computer usage, it is now common for companies, even the smaller ones, to require landlines and computer input/receiving terminals. These terminals can be located efficiently only if the following considerations are taken into account: the company's need for the terminals, how they will be used, and the classification of the information they will receive or transmit. The executive involved in office planning must work with either the IT Director, or consultants, or both to determine how many of these units will be required, where they will be located, what power sources are required and what allowances must be made for future needs.

Postal Service

Initially, when either an increase in the activity of the organization is being contemplated or relocation to another area is under consideration, the planner should make sure that the postal service in the potential or current location, whichever is appropriate, will be able to cope with the increase in volume this action will generate. Members of the Post Office's customer service division can be very useful in such evaluations. They can arrange to send a representative to the company to discuss the plans and to suggest methods by which the increase can be handled.

Relocation or reorganization also presents the opportunity to bring your company up to date in its postal operations, and the executive must always bear in mind that services vary from area to area in efficiency and availability. If the company uses independent courier or delivery services, the ability of these services to cover the proposed expansion or relocation needs must also be fully explored to allow the planner to implement systems that ensure continued or improved efficiency.

Client Service Areas

When considering the office complex in terms of what image the company will project to visiting clients, the planner will find that identifying the areas that will be seen by visitors is extremely useful. All too often, the reception area is counterproductive to a company's image, in that the impression of luxury, cleanliness, and efficiency to which clients are introduced immediately upon entering the building is counteracted as they proceed through less impressive areas. Potential clients must gain from their visit the belief that the organization is efficient, functional, and humanly satisfying.

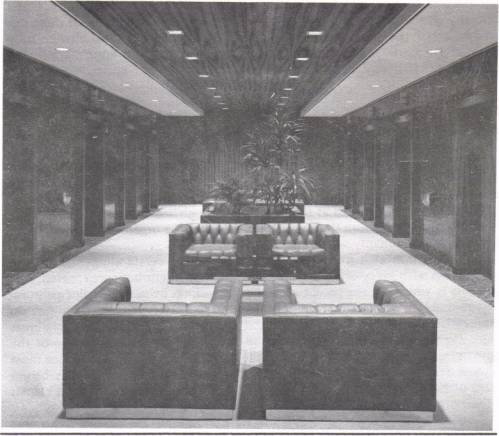

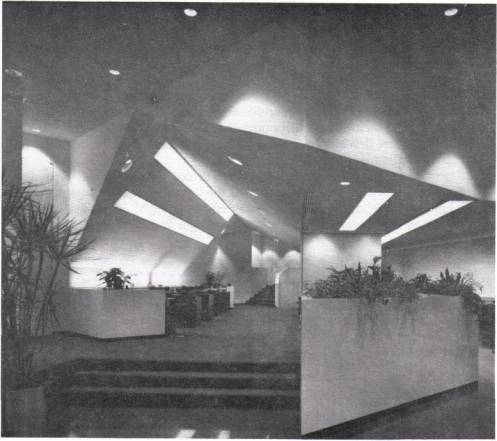

The reception area must be created with the understanding that it is in competition with every other building the potential client has ever entered. Perhaps this is why so many reception areas in buildings owned by major corporations resemble more closely luxurious hotel foyers or art galleries than they do commercial offices (see Exhibits 1-2 and 1-3).

Employees who work in areas where clients will be received should be instructed in the importance of the company's image, even to the point of their appearance and speech. Since most in-house employees rarely, if ever, visit competitors' buildings, they may be unaware of the importance a company's environment can play in the sales efforts their organization.�

Corridors through which clients will walk should not be allowed to become meeting places for junior staff on coffee breaks. These areas should be cleaned more often than any other part of the building and maintained with greater attention to detail; they should also be decorated in relation to the entrance area.

The office planner should also take into account the condition in which most visitors will arrive at the building. They may have traveled long distances; therefore, rest room facilities and refreshment should be considered. Providing a visitor with the opportunity to freshen up before an interview can have a very positive effect on a company's interaction with its clients. The company that greets its guests with a hot drink in tasteful china, served with a smile, stands far more chance of gaining the assistance of that visitor or of receiving an order than the company that asks visitors to search around back passageways for a vending machine that will serve them (if they have the proper change) a lukewarm cup of indistinguishable liquid in a polyurethane cup.

Another point often forgotten by executives planning a building is that, although they and the staff have the time to discover where various departments are located, the visitor arrives without any knowledge of the building at all. Quite often, a visitor may not even speak the language of the workers in the building. Signs, therefore, are very important for putting the visitor at ease. Many companies operating international businesses today issue to visitors a small booklet that contains a map of where they will find various departments and individuals. Unfortunately, a smiling company representative who greets foreign clients (who do not understand the language) by pressing a booklet into their hands is more likely to lose the order than to obtain it.

Clearly, executives involved in office planning must continually remind themselves that the most important people in the building at any time are those people whose financial investments enable the organization to be there - that is, the clients.

EXHIBIT 1-2���

Client Service Area - The Lobby

\

Employees of any business need to be able to relate to that business. More than anything else, they need to be able to relate to the environment in which they work. Executives contemplating any action in the field of office planning must realize that they will need the assistance of a consultant in behavioral psychology. Even before a behavioral psychologist is retained, however, certain basic steps will ease any changes within the company brought about by reorganization.

Whether

a single department is being reorganized or the entire company is being

relocated to another town, the employees involved should be kept fully

informed;

otherwise, they will be forced to rely on rumors. Up-to-date information

can most easily be conveyed in a newsletter format. If the company already

has a regular newsletter, the necessity for the move or reorganization should

be gently fed into the content of the newsletter over a period of time,

culminating in a full explanation of how the move or reorganization will benefit

the staff.

If the company does not have a newsletter, a brochure can be produced in association with the companies and consultants the firm is retaining, to explain in detail exactly what will happen to the employee's environment. In addition to this brochure, follow-up information should be conveyed by regular memorandum or letters, either directed to the individuals concerned or posted on the notice board, and, in association with this introduction, general meetings should be arranged at which the staff can learn what is happening and pose personal questions. The executive involved in planning should also conduct regular meetings with the heads of departments to gain insight into the reaction of their employees to proposed changes. These insights can then be fed back to the designers and decision makers to ensure a minimum of discontent.

Public Relations���

The reorganization of an office and, more especially, the relocation of an organization is news that can be used to the benefit of any company. It can place the company's name before potential clients, as well as potential employees presently working for competitors. It is good sense, therefore, that the public relations department or consultant is kept well informed of what is happening and that photographs are made available as soon as possible.

Keeping a diary of events from the original decision to move to completion of the project is also extremely useful. Such a diary can be used at a later date to create a summary, either in audiovisual or brochure form, that will become a tool for the personnel department when recruiting new staff. Many companies make the mistake of photographing only the finished job. This has far less impact than a complete program that presents photographs taken before, during, and after the project's implementation.

The public relations value of an office planning scheme can exceed 50 percent of any company's advertising budget, if information about the plans is released to the media with skill. Trade and professional magazines, covering the industry to which the company belongs, will normally accept, with pleasure, details of any major office change. In addition, local newspapers, design magazines, and similar general circulation media can usually be expected to recognize a public interest in interior changes within any organization.

Instructional Programming - Chapter One

Instructions: Here is the first segment of instructional programming in this course. Answering the questions following each chapter will give you a chance to check your comprehension of the concepts as they are presented and will reinforce your understanding of them.

As you can see below, the answers to each numbered question are printed to the side of the question. Before beginning, you should conceal the answers in some way, either by folding the page vertically or by placing a sheet of paper over the answers. Then, read and answer each question. Compare your answers with those given. For any question you answer incorrectly, make an effort to understand why the answer given is the correct one. You may find it helpful to turn back to the appropriate section of the chapter and review the material you were unsure of. At any rate, be sure you understand all the questions in each segment of instructional programming before going on to the next chapter

1. An organization is only as efficient as:

(a) the president of the company.

(b) the equipment housed within the company.

(c) the professionals and staff employed within the company.

(d) the communication that exists between management and employees.

2. No organization needs to have its own training facilities when it can rely on outside consultants and colleges.

(�� )� True

(�� )� False

3. A company should not consider relocation unless it is sure that workers required to suit its needs live where the company will be relocated.

(�� )� True

(�� )� False

4. Most organizations will tend to remain where they are primarily because of the difficulty in trying to conduct their business while organizing a new base of operations.

(�� )� True

(�� )� False

5. Executives involved in office planning should consider the means of transport used by staff to commute to the office:�

(a) as a number one priority.

(b) as a matter of little consequence.�

(c) as it relates to efficiency, work, and productivity.�

(d) as a duty of the company.

6. For reasons of efficiency, every member of the staff should have access to telephones and internal communications.

(�� )� True

(�� )� False

7.�Staff should be _______________ to be seen in public areas.

(a) encouraged

(b) not encouraged

(c) expected

(d) banned

8.�� Reception areas should be:

(a) no more impressive than the rest of the offices.�

(b) luxurious.�

(c) reflective of the image that the company wishes to project.�

(d) all of the above. �

9. Reorganization or relocation of a company's offices is generally ___________ for public relations. �

(a) bad�

(b) good�

(c) unimportant�

(d) essential

10. Investigating the company's postal needs is the responsibility of:�

(a) the company.�

(b) the post office.�

(c) the government.�

(d) all of the above.

11.� When relocating an organization's offices to another site, the planner need not consider residential real estate availability.

(�� ) True �

(�� )� False �

12.� Implementation of a training program can best be achieved by closing down the operation and organizing the proper space.�

(�� ) True�

(�� ) False�

13. During the reorganization or relocation, productivity will: �

(a) rise.�

(b) remain about normal.�

(c) drop.�

(d) first rise, then drop.�

14. With respect to communications planning, incoming calls must always have priority over internal communications.

(�� ) True�

(�� ) False�

�15. The sales department should have separate receiver/trans�mitter systems for processing orders.�

(� ) True�

(� ) False

16. In recognition of the fact that employees with enhanced technical skills and educational qualifications are an asset on the job, more and more companies are finding it necessary to institute their own in-house ______________ programs.�

Answers

�

Chapter Two:�Office Planning & Design

Preliminary Preparation

�

Facility planning is exciting, it gives those involved a power, and it provides physical results to their actions and decisions. The real goal of such undertakings, however, must never be allowed to disappear: Commercial facilities must serve the actual needs of the organization for which they are created. However glamorous the results, they must first and foremost be good design.

What is good design? Ask a cross section of office workers, and most of their definitions will be 90 percent aesthetic. An office planner's or facilities manager's definition is more realistic: Good design is the combination of efficiency, economics, function, logistics, and aesthetics. Therefore, before anyone can judge good design, all the needs it was created to serve must be considered.

This chapter is designed to show the executive involved in planning exactly what information must be collected or considered before any specific layout or design decisions are contemplated. Because the material covered herein is essential to a thorough understanding of the rules behind the discipline of office planning, this chapter will require more study than any other part of this course. How the procedures described in this chapter fit into the overall planning pro�cess can be further clarified by studying the "Space Planning and Design Procedures Outline" presented in the Appendix (part 1, in particular).�

Some

Planning Realities

�

Logically, an organization can be expected to function most effectively if the space in which it is housed has been designed according to the most efficient layout possible for its operation. Most office functions, however, are assigned to arbitrarily shaped spaces that have been "adapted" to those functions.

This situation results from the fact that most buildings are designed and constructed according to the lowest common denominator - that is, to fulfill the facility requirements of as many different tenants as possible - to ensure the financial return on the investment of the developer or owner.

Ideally, every building should be designed "from the inside out," so that the shell is merely the covering of a purposefully designed layout custom fitted to the needs of the occupant. But since this rarely happens, the executive in charge of locating office facilities must learn to adapt existing buildings to the individual needs of the company.

The provision of office facilities is one of the most important decisions any organization ever makes. Therefore, such a decision should be based on the best input of advice and experience available. Since changes in major facilities are normally made only once in a decade, if that often, most organizations do not possess the knowledge and experience required; if this is the case, outside help should be sought.

The old adage, "There is nothing new under the sun," may be a little over�stated, but many administrational problems would indeed never arise if the solutions employed by other organizations were thoroughly investigated beforehand. This is doubly true in today's world of accelerating technology and business systems. A study into what organizations operating in the same, or similar, fields are doing to solve the same problems will always be useful and, in some cases, may suggest ways in which even the latest methods and systems can be improved.

Each organization should also evaluate how its needs differ from those of other organizations. The solutions to one firm's problems may be aesthetically desirable but completely impractical when applied to those of another company. Possibly one of the greatest mistakes in office planning was made in the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s, when thousands of individual organizations adopted "open plan" solutions as a way to cut construction costs and reduce the square footage needs of their staff. Although the idea was perfect for some commercial situations, it failed miserably in others. The current trend to employ system furniture may also be similarly viewed in the future as a fashion that was indiscriminately used by facilities executives. Indeed, many of the present day technological advances are better served by custom-made and individually designed work units. Therefore, careful evaluation of what an organization does and what would best serve its needs is essential to effective office planning. �

Analyzing The Existing Administrative Organization �

Before making a decision, whether about a change in layout or a relocation of the organization's office facilities, the planner should first obtain certain working information. The data assembled at this stage will allow the planner to make the right decisions as the job proceeds. The following data should be compiled:

1.�� A profile of existing facilities within the organization for the divisions and departments concerned. This should contain such information as:

(a) square footage used per job function ;

(b) interaction between personalities within the unit concerned;�

(c) equipment presently employed.2. If possible, comparisons of space and layouts employed by other organizations similar to the planner's own should be established.

3. In-house or commissioned reports that have been prepared in the past concerning the unit involved should be analyzed and collated.

4. Expansion or contraction expectations of space requirements should be established.

5. Company policy statements relative to similar or comparable past actions regarding facilities for the organization that might have a bearing on the new facility and its operation should be analyzed and collated.

6. A human resources profile on the individuals involved, outlining their potential contribution or obstruction to possible changes through expansion or relocation, should be produced by department heads. �

With these facts and viewpoints collated, the planner should be able to evaluate all available options and to apply this knowledge to choosing space without making major policy or administrational mistakes. �

Evaluating Space Options

To evaluate all the available space options or to reorganize existing space, using the established data base, the planner and the other decision makers involved should consider the following questions:

1. Do the areas provided by the available room shapes and structures increase potential efficiency and personnel satisfaction?

2. Can the space under consideration absorb expected expansion? And can it be redesigned at minimum cost to accommodate contraction, if necessary, without affecting efficiency?

3. Can easy communication links be established with other departments and locations?

4. What is the relative cost of adapting the space to the established requirements?

5. Does the space offer greater efficiency potential than either the existing space or other available options?

6. Will it serve a permanent, a long-term, or a short-term solution to the organization's present problems or needs?

7. Does the proposed location fit the time schedule requirements with respect to acquisition, furnishing, and moving in?

8. Will the property add to, or detract from, the image and status of the organization? �

The organization's responses to these questions should be organized in a preliminary listing before any preliminary decision is made to acquire property or to issue a statement of intent. In addition, the planners should consult the most experienced and qualified help their organization can provide or can afford to hire before any binding decision is made, if only to save remedial costs at a later date. �

Establishing Organizational Type

To evaluate how well any available space options will fulfill organizational requirements, the planner must categorize the firm according to organizational type or combination of types. Input from department heads with respect to the following questions provides invaluable information for these preparations:

1. How many structural layers, in terms of authority and/or function, are there in each department of the organization (for example, managers, foremen, or supervisors; skilled staff; clerical staff; operators; unskilled workers)?

2. How do these functions interact with each other?

3. Is the department or unit a multifunctional group with total internal communication and interdependent activity (for example, a buying office or a mailroom)?

4. Within the department or unit, are these several layers of autonomous authority that are not privy to the same depth of information (for example, an accounting department)?

This information is essential for deciding about layouts and the amount of visual and acoustical privacy required throughout the facility.

The planner must also establish, by department, division, and unit in the organization, such factors as the size of working groups in any business function; the need for face-to-face communication; the need for client consultation in privacy; the amount of interaction between organizational units; the need for intradepartmental communication and control; and the appropriate image required for the status levels of the executive staff so that the image projected coincides with the expectations of clients, suppliers, and the staff with whom the executives have regular contact. In brief, a very clear picture of the organization must be established - how it is structured, and why; how it functions; and how it compares with competitors and associated organizations.

Categories Of Facilities Space �

There are many types of facilities space, but basically they fall into the following five (5) categories: �

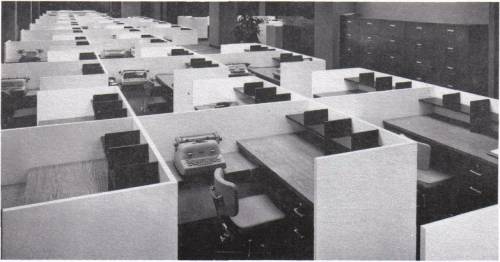

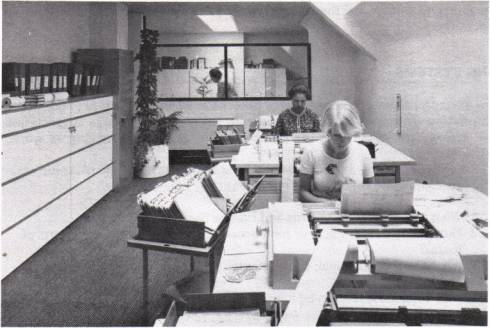

1. Open plan: All functions of the administration of either a total organization or a department are housed in a single area or room (see Exhibit 2-1).

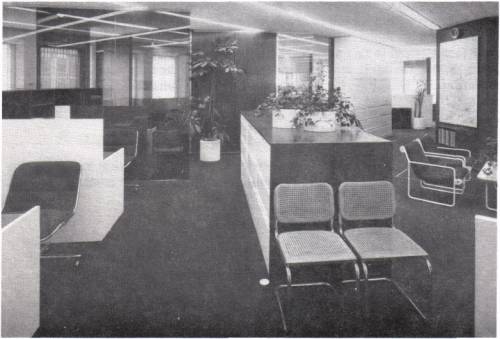

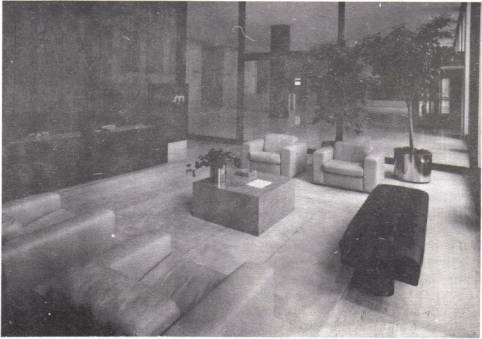

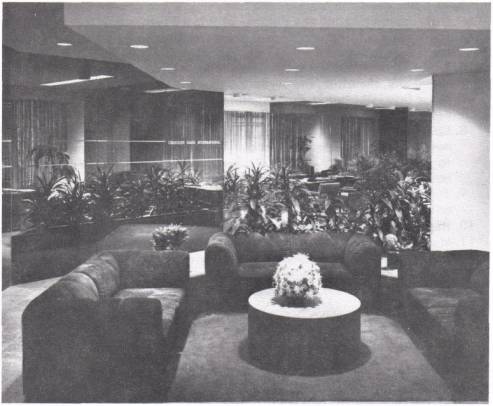

2. Landscaped: This system modifies the open plan format. Some functions are housed in separate rooms that feed into the main area (for example, executive offices, conference rooms, and so on), and screens and large planters are used to separate functions and units of the organization (see Exhibit 2-2).

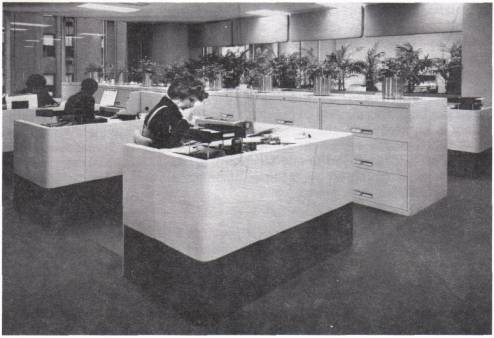

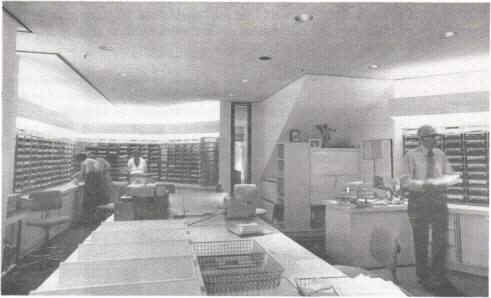

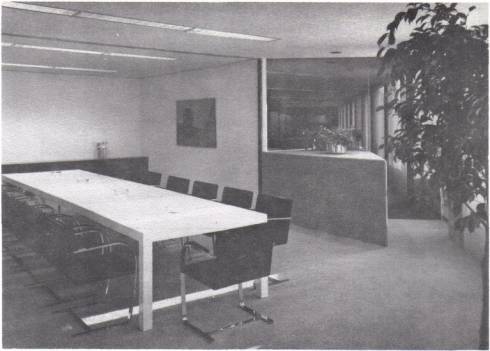

3. Departmental: This system is based on the theory that each department is an individual unit. Each department of the organization is treated separately and given its own reception, conference, accounting, and human facilities (see Exhibit 2-3). This system provides individual security for each department, as necessary. Within each department, the open plan, landscaped, or cellular approach can be employed.

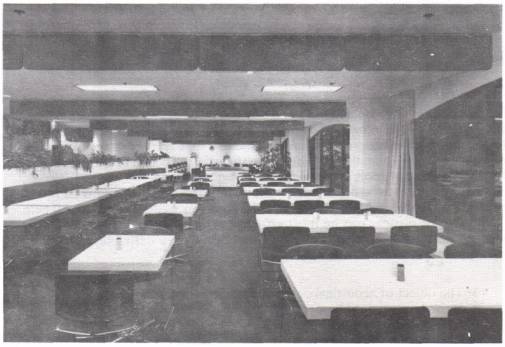

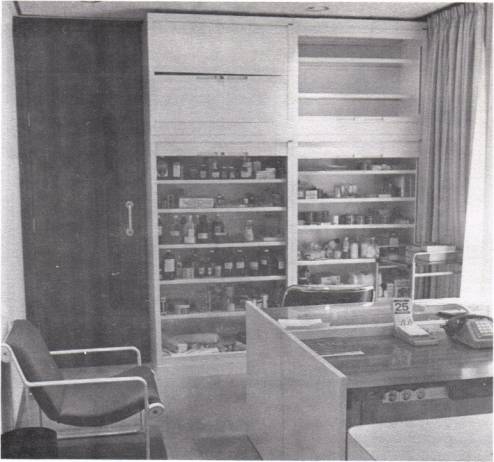

4. Cellular: This system is still the most common in small and medium sized companies. Under this system, many secure separate rooms, each devoted to one aspect of the organization's operation, are usually linked by a corridor system or a central reception area (see Exhibit 2-4).

5. Group function: This system creates many medium to large areas that are semi-independent of all other areas. The theory behind this approach is that each area should be dedicated to the use of a group of workers who need to interact with each other without distraction from other groups (see Exhibit 2-5).

EXHIBIT 2-1��� Open Plan Office

EXHIBIT 2-2��� Landscaped Office Plan

EXHIBIT 2-3��� Departmental Office Plan

EXHIBIT 2-4��� Cellular Office Plan

EXHIBIT 2-5��� Group Function Office Plan �

No matter which of the five systems of office planning - or permutation of these systems - is chosen, many factors other than the layout will have a bearing on the success or failure of the planning program. All too often facilities planning is undertaken without a full in-depth knowledge of the needs of the total organization. While an individual department's facilities may be a success, these very same facilities can in fact at times detract from the overall efficiency of the total organization. The application of the facilities plan to the total needs of the organization should, therefore, be carefully analyzed and considered.

Corporate image, group buying, and interactive needs also have a strong bearing on many planning and design decisions, as detailed below.

Corporate Image. A corporate image is established through the standardization of all design decisions. This affects everything that can be considered a design factor, thereby producing standardized (1) letterheads, logos, type styles, and sizes of all company stationery; (2) company liveries (including signs, vans, nameplates, and so on); (3) styles and types of furnishings and furniture; and (4) uniforms, company magazines, and even office layouts. Because of such standardization - that is, because of the corporate image projected - every property, business activity, and product of the company is immediately identifiable as part of that organization. �

Group Buying.� This method of purchasing anything from raw materials to typewriters is controlled at the corporate headquarters, or buying division, and allows the company to benefit from bulk order discounts. Sometimes, group-buying plans are employed simply to control capital expenditures and supplier relationships. With respect to facilities planning, group buying can limit the choice of possible supply points. �

Interactive Needs.� Possibly the greatest problem area for the facilities planner who is making supply or design decisions concerns the interactive needs of facilities located at different sites. In a multi-location facilities application, the planner must take into account that paperwork produced in one office should be applicable to the systems employed elsewhere; that equipment at one location must be able to use the output of equipment in other locations; that systems of filing and accounting must be standardized; and that communication systems must be uniform, or at least usable, throughout the organization.

Categories of Facilities Applications

Facilities applications introduce the various outside factors that have a bearing on the success of any given office-planning program. The most common facilities applications are:

1. Multi-location.

2. Multi-purpose.

3. Stratified.

4. Estate or campus.�

5. Interactive (controlled).

6. Interactive (non-controlled).�

7. Single-level simple.�

8. Tradition based.

9. Acceptance controlled. �

10. International.

Let us examine these applications in depth and show how they can control many of the decisions made in the initial stages of facilities provision. In fact, many of these factors are built into a corporate design brief before the facilities executives become involved with the project. �

Multi-location Application

One hundred years ago, it was common for most organizations to be located in one place, and any other geographic locations that were under their control were not regarded as part of a total corporate image. Thus, in the past, office managers involved in facilities decisions had to consider only the requirements of a single, protected locale and needed little knowledge of what was done 200 miles away, in another state or another country.

Today, however, economic limitations, the need to transfer people and functions to other locations, and the awareness of the value of a corporate image have created in many cases a standardization of facilities throughout many organizations. Therefore, it is almost impossible to undertake the provision of office facilities without reference to existing off ice facilities in use by the same organization in other locations. Similarly, if an innovation that increases efficiency or staff satisfaction is introduced at one location, then that innovation may have to be introduced at other offices within the organization, as well. Company policy regarding group buying of equipment and furniture can also limit the actions of the office planner for economic reasons. Therefore, in a multi-location organization, the planner should undertake a comparative analysis of all facilities and should try to determine how actions in one location may affect all other facilities in the future.�

Multi-purpose

Application

Today, many organizations are involved in a myriad of commercial undertakings, all of which have differing operational needs and varying degrees of dependence on the mother company. To ensure efficiency, the office facilities of the mother company, or the corporate headquarters of such an organization, must accommodate all these various needs. In some cases, one office facility located in one building may have to serve several disciplines or commercial undertakings. In such a situation, the planner must investigate each of these operations independently before making any planning or design decisions.

Stratified Application

Because of the rising costs of land and the need for more and more companies to obtain center-city premises, the construction and use of multistory buildings has become common during the twentieth century. Yet many planning decisions are made without full consideration of this development. Behavioral psychologists have established that few employees perceive the multistory context of their work environment - that is, they rarely, if ever, consider the fact that business is being conducted above and below them in parallel to their own activities. Furthermore, many people fail to realize that the population of many office buildings is larger than that of entire towns of the past. The technological advances of building and city operations have left most of us far behind in terms of comprehending the complexity of our environment, yet the facilities planner must strive to include these factors in every decision if he or she is to design a plan that will produce maximum efficiency.

Estate or Campus Application

It is not uncommon for an organization to occupy several buildings on the same site, especially in the case of academic, government, or institutional facilities. The executive in charge of facilities management in this case must build up a knowledge of these various buildings and remember that actions taken in any one of these buildings will affect the efficiency of communications with, or staff morale, in the others.

Interactive (Controlled) Application

Some office facilities are created to administer rather than to direct. This is particularly so in the case of government offices or institutional branch locations, where the activity of the organization exists to carry out the directives of an absent executive council or director. The business of such facilities would normally be described as "passing on" directives or assistance to non-organization people. �

In such cases, the office facility must be created to serve this administrative function and is usually planned according to an existing set of systems and opera�tions. A local post office is a perfect example of this situation. The local facility has a manager and a staff, but the operational systems are developed elsewhere, and all executive directives are issued from the national headquarters. �

In these cases, the planner/designer must create a facility that will be totally compatible with other such facilities - it must be able to operate with the same equipment and forms and in the same situations as all other such units. Within such parameters, the planner can use his or her ability only to improve upon the basic facility and the designer can only affect its aesthetics. �

Interactive (Non-controlled) Application

In an interactive (non-controlled) application, as much as two-thirds of the area being planned will be used for client occupation or goods display; and the office facility, although operating as part of the facility, will be located in the remaining space, separated by some form of "people barrier."� Banks, customer offices, sales offices, stores, and the like often require such arrangements. The planner, therefore, must determine not only the requirements of the organization but also those of visitors, clients, customers, and so on.

Single-Level Simple Application �

This application needs little description except to say that, in this situation, the facility operates on one floor, in one location, and fulfills the total administrational needs of the organization.

Tradition-Based Application

A tradition-based application is not necessarily a single application. In fact, in most cases, it will be an addition to one or more applications. This situation exists when an organization is obliged to place several restrictions on, or give definite guidelines to, planners and designers alike, based on state-of-the-business functions. For example, architects need drawing boards and prefer to work near a window; doctors wish to interview their patients in a private room rather than in a common reception area; and lawyers demand privacy when dealing with clients. No matter how much capital expenditure might be saved or how much efficiency of the overall operations might be improved if tradition-based rules were ignored, the possible (or probable) loss of income or staff would not permit such innovations to be implemented without a great deal of righteous argument.

Acceptance-Controlled Application

Just as tradition-based applications refer to what the employees of an organization will accept, acceptance-controlled applications are dependent upon what people outside the organization (most often, clients) will accept. Most clients of any organization come to the firm because they choose to; therefore, too great a change in that organization may drive away some clients. If Mr. Anderson, for example, has always discussed business with his account executive in a private and comfortable room over a cup of coffee, he may well disappear if he is made to wait in a communal area and then conduct his business in competition with several other concurrent conversations. Therefore, planners should take great care in discerning why the company's clients prefer the company to its competitors, and, once these factors are established, they should be amplified or perfected. Certainly, the planner should not eliminate or replace them without giving very careful thought to the outcome.

International Application

If the main activity of any office facility is to do business with foreign countries or clients, everything must be considered in this light. Provision must be made to make the foreign visitors welcome and comfortable. Communications equipment, and so on, must be compatible with the equipment in other countries, where necessary.

Selecting the Building or Space �

Once the planning executives have established the type of organization they are trying to accommodate and have determined what the most efficient system of planning is in relation to the facilities they wish to provide, their next step is to select the building or to adapt the building that is available. The building (or buildings) available for consideration should be examined to see if they can be adapted to serve the needs of the organization.

At this stage, planning executives will require the input and advice of an architect and a structural engineer in addition to that of an office planning expert. The most perfect situation would be to continue through the design and space-planning process until an interior layout is established and then to commission a shell to be constructed around this "perfect office." This approach, however, is rarely adopted, although in the last decade or so many organizations are concluding that this is, indeed, the best way to provide an office facility, whatever size the project.

If, however, an existing building must be used, or if a choice among several available buildings or sites must be made, then the planner must investigate the following: �

1.��Commuter status: How accessible is the building to the staff (regularity of public transport, density of road traffic at the time the staff will be arriving or departing)? �

2. Updating costs: If the building is not new, there may be heavy costs in�volved in bringing the building up to standard and in complying with building regulations and conservancy laws not in effect when the building was built.

3. Area image: Will the reputation of the organization benefit from being in the building under consideration, in terms of the image the location projects to both the organization's staff and its clients.

4. Communications value: The value of the building must be established in terms of whether it moves the organization into or away from the organization's sphere of business activity (for example, a newsstand outside a cemetery will do less business than one outside a busy railroad station). The building chosen must be accessible to the organization's everyday business activity, or it must be chosen for more reasons than that "it is a good building."

5. Running costs: The planner must take into account every cost that will be incurred, by the organization and its staff, once the facility is in use. How much will it cost to reimburse staff for travel costs? What maintenance costs are probable? What will be the cost of light, heat, air conditioning, and so on? How long will the building serve the organization's needs relative to the necessary investment costs? �

The planner should also establish what the organization's present needs for storage spaces are, and what future needs may be (the possibilities of microfilm and other storage methods should be investigated). Does everything need "secure" storage? It is wise to classify everything that needs to be stored within the building into levels of required security, as follows: class 7 = storage vault; class 2 = fireproof storage cabinets; class 3 = locked filing cabinets; class 4 = classified information kept in locked drawers in executives' desks, and the like; and class 5 = non-classified material.

An important consideration, often not examined until the actual interior design begins, is the weight load of the floors of the space involved. All buildings have a recommended dead weight loading for floors. In the case of some buildings, these figures may have been forgotten or lost with the passage of time. Detailed information about what equipment can or cannot be used because of its weight is something that must be established before any space planning can begin.

Judging the appropriateness of available buildings, spaces, and sites is a complicated matter. Many more factors need to be taken into account than those that are normally voiced in the general board meetings that decide that new facilities are required.� An organization's space needs fall into four categories:

1. Work areas.

2. Public areas.

3. Service areas (rest rooms, elevators, and so on).

4. Storage areas.

The planner, having established how the organization currently uses its spaces, will be able to apply this knowledge in determining the appropriateness of the building under consideration and in planning how to use the new space efficiently. Any available data regarding the organization's expansion needs over a predetermined period of time must also be taken into account.

Quite often, office buildings classify available space according to only two categories: service areas (elevators, rest rooms, entrance lobbies, and soon) and huge work areas (airplane-hangar type rooms). The costs of creating a working environment that satisfies the organization's needs (partitions, cost of setting up these partitions) must be carefully evaluated before any building can be deemed suitable for the company's needs.

Analyzing Departmental Needs

It is usually very difficult to establish in detail what the norm is for off ice facilities for any given area or business activity. Obviously, firm A's competitors are not likely to open their operations to a planner from firm A.� While members of firm A's staff who have worked for competitors may be able to supply some useful information in general terms, they most likely will offer only vague criticisms and comparisons. Few people in any organization ever actually take a tape measure to their own work station, let alone know the technical details of equipment and furniture. For this reason, the planning executive may need to consult a professional office planner. The professional has probably worked on similar projects and will know what to analyze to achieve the best results.

In general, the executive involved in office planning should evaluate departmental equipment, systems, and general space requirements according to the�procedures detailed in Exhibits 2-6 and 2-7. (Actual space standards are discussed later in this chapter, as are staff preferences.) �

EXHIBIT 2-6��� Procedures for Analyzing Present Facilities

For each department, list the following data, subdivided into sections within the department, where possible: �

1. Determine the total number of people employed in the area. �

2. Computer average space per person in square feet in the existing facility. �

3. Determine actual territory per person. �

4. Compare answers to questions 2 and 3 and ask department heads to evaluate (generally) the performance of individuals relative to the space they use. You may find that space has no effect on individual productivity; or you may find the opposite, which will help you assess space standards and furniture requirements later. �

5. Draw up lists of existing furniture and equipment. �

6. Evaluate, with department heads, requirements for extra furniture and equipment in the new facility. �

7. Evaluate conference facilities (including interview rooms and training facilities) that will be required. �

8. Establish number of rest rooms, personal lockers, and clothes closets that will be needed. �

9. Evaluate refreshment facilities - that is, restaurants, lounges, vending areas, and so on - in terms of the total space required. �

10. Add space requirements for filing and storage. �

11. Calculate square footage of existing corridors and passages. �

12.� Calculate square footage of existing reception areas.

13. Calculate capacity of present car-parking areas. �

14.� Establish the space standards that existed when the existing premises were first occupied. �

EXHIBIT 2-7��� Procedures for Analyzing Staff Space Requirements �

Evaluate every member of the proposed staff according to the following checklist: �

1.��� Visual privacy is:

(a)������� absolutely essential.

(b)������� important.

(c)������� useful.

(d)������� not required.2.��� Acoustic privacy is:

(a)������� absolutely essential.

(b)������� important.

(c)������� useful.

(d)������� not required.3.��� Contact with clients or visitors is:

(a)��������on a regular basis.

(b)��������occasional.

(c)������� not often.4.��� Contact with other staff in conference is:

(a)��������on a regular basis.

(b)��������occasional.

(c)������� not often.5.��� Job or equipment used requires:

(a)������� privacy.

(b)������� noise control.